A Gospel-Shaped Framework for Christian Civic Engagement

I am indebted to Justin Giboney’s book Compassion and Conviction [1] and Timothy Keller’s book Generous Justice [2] for many of the ways I think about Christian civic engagement. I encourage you to spend time reading both of them.

Many Christians today feel caught in the middle of a cultural storm they are unsure how to navigate. We were already feeling this tension before the recent crisis caused by our federal government’s immigration enforcement strategy, which intensified over the last month. We feel a responsibility to care about what is happening in our city. We read stories about families being separated and the excessive use of force, and we don’t know what faithfulness looks like in the midst of it all.

When it comes to the elected officials charged with pursuing the good of our city, state, and nation, many of us feel disillusioned by the current political environment. Some respond by getting pulled into a political agenda. Others respond by disengaging altogether.

At the same time, we intuitively understand that what is happening in our city goes beyond mere politics. We are not only asking questions about immigration policy, but about human dignity and the use of power. We can take responsibility to love our neighbor without surrendering to a political agenda. We can affirm the role and responsibility of government without being discipled by partisan narratives. We can say that the excessive use of force by federal authorities is wrong without engaging in political posturing.

Over the last month, the pastors of River City have received several requests to help people process what is happening. Many have asked practical questions about how to love their neighbors and how to care for their own souls in the midst of all of this. But those practical questions often give way to something deeper. People long for a gospel-shaped framework for civic engagement.

Many Christians are struggling not only with what to think about the present situation, but how to think about it as followers of Jesus. In this article, we want to offer a Biblical framework to help you think, pray, and act faithfully in a complex civic moment. Christian civic engagement does not begin with politics. It is fundamentally a discipleship question.

Love of Neighbor is the Non-Negotiable Starting Point

Civic engagement is not optional for Christians, but it is also not ultimate. It does not look the same for everyone. We are not all called to vocational political work, but we are all called to love our neighbors, and one way we do that is by caring about civic policy and practice.

Not all Christians throughout history have lived in political systems where they had a voice. We do. And the decisions and policies of our leaders have real consequences for the good or harm of our neighbors. Loving our neighbors means we cannot ignore that reality.

The Biblical vision of life in this world always holds together two realities: our eternal hope in Christ and our call to love our neighbors in the present. Scripture never allows us to choose one at the expense of the other. We are citizens of heaven (Phil 3:20), awaiting a kingdom that cannot be shaken (Heb 12:28), and yet we are sent into the world to bear witness to that coming kingdom through lives of faithful love (Mt 5:16).

Though we are exiles and sojourners in this world (1 Peter 2:11), we are still called to seek the welfare of the city where God has placed us (Jer 29:7). We do this because our hope in God’s future frees us to love sacrificially in the present, not because we believe we can usher in the kingdom of God through politics. Knowing that Christ will judge the living and the dead (2 Tim 4:1), we care deeply about justice, dignity, and mercy now, without confusing them with ultimate salvation.

Every neighbor we encounter is made in the image of God and therefore possesses inherent dignity and worth. This includes the neighbors we like and the ones we don’t. It includes refugees, immigrants, and sojourners. It includes those who followed legal processes to enter our country, and those who did not. It includes elected officials who will fail us and those who will serve faithfully. It includes federal enforcement agents and those who protest against them. All of them will one day stand before God, just as we will (Rom 14:10-12).

We must never lose sight of the dignity of the person across from us or beside us. This is why we pursue the common good of our city, not merely the Christian good. Jesus reminds us that our love for the vulnerable is not separate from our eternal destiny: “As you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me” (Mt 25:40). The present crisis is doing real harm to real neighbors. If we love our neighbors and believe in the coming judgment and restoration of all things, we cannot be indifferent to what harms our city.

Love of neighbor is foundational to Christian civic engagement. It motivates us to act in the present, and it also creates guardrails that keep us from confusing political action with ultimate hope. We engage faithfully now because we trust God fully with the future.

Why the Political Age Is a Bad Discipler

Much of the confusion among Christians today comes from allowing the political age to disciple us. Scripture tells us not to be conformed to this present age, but to be transformed by the renewing of our minds (Rom 12:1-2). Political movements seek our loyalty, shape our imagination, and train our instincts, but they are poor disciplers. If we listen to them long enough, they distort our loves and poison our witness.

Political movements seek our loyalty, shape our imagination, and train our instincts, but they are poor disciplers.

The false dichotomy of our age

We have been presented with a false choice between two political poles. These opposing camps reinforce a system where loyalty is demanded, complexity is punished, and outrage is rewarded. Yet neither pole represents Biblical faithfulness.

In 2018, the Hidden Tribes study found that public perception does not reflect political reality. While the loudest voices tend to be on the extremes, between 70-85% of Americans fall into what researchers call “the exhausted majority” [3]. Most people are weary of the fighting and long for real solutions to real problems affecting real people.

The confusion among Christians

Christians have not been immune to this polarization. Significant portions of the church have not only aligned with political extremes but have become mouthpieces for them.

Among white evangelical Christians, support for Donald Trump and the Republican Party has been extremely high. Among white liberal Christians and Black Protestants, support for the Democratic Party has also been extremely high. When Christians split along these lines, the result is deep confusion, especially for younger believers.

I have spoken with many younger Christians who grew up in white evangelical homes where being a Christian was implicitly, or explicitly, equated with being a Republican. One recently told me they remembered an uncle saying, “I don’t know how you can be a Christian and vote for anyone other than a Republican.”

Many in the emerging generation now feel politically homeless. They see real flaws in both conservative and progressive movements. When political loyalty demands full platform adoption, faithfulness feels impossible. What if I agree with some conservative convictions, some progressive convictions, and hold beliefs that don’t fit either camp?

For many young Christians, across race and political background, the politicized Christianity they inherited does not ring true, yet the alternatives they are offered don’t feel faithful either. Some disengage, not because they don’t care, but because they don’t know where to stand. Others swing from one extreme to the other, only to discover the same shortcomings.

Joshua Harris, who publicly announced he was no longer a Christian in 2019, recently described his experience when he reflected on leaving conservative evangelicalism only to find himself unsettled in progressive spaces as well:

“I started noticing the same ‘bully energy’ in progressive spaces that I’d experienced in conservative ones… a different orthodoxy, a different list of correct beliefs that made you righteous and acceptable… I thought I had left a high-control environment. But I had mostly just joined a new one” [4].

When the church borrows the categories of the age, it consequently inherits the confusion of the age.

This is Not a Call to Passive Neutrality

Rejecting political extremes does not mean moral indifference or simply settling somewhere in the middle of the political spectrum. This is not a call to passive neutrality or settling for the absence of tension.

Martin Luther King Jr’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail, warns against this temptation. As he confronted injustice, many white Christians, whom Dr. King called “the white moderate,” urged patience, not because they opposed justice outright, but because they preferred order. King called this “negative peace,” which is the absence of tension without the presence of justice [5]. Biblical love refuses that bargain.

Faithful presence is not passive presence. If we are to engage faithfully, we need a positive vision rooted in the gospel.

Compassion and Conviction as a Gospel Posture

If Christians are going to be a transforming presence in our city, we must have a positive vision of civic engagement. We cannot just define ourselves by what we are against or what we are not doing.

At River City, our vision for Christian civic engagement is grounded in the inseparable union of compassion and conviction. Together they form one of our values as a church, because we believe the gospel calls for compassionate hearts informed by Biblical convictions. These are not competing values. They are gospel realities.

The positive tension between the two

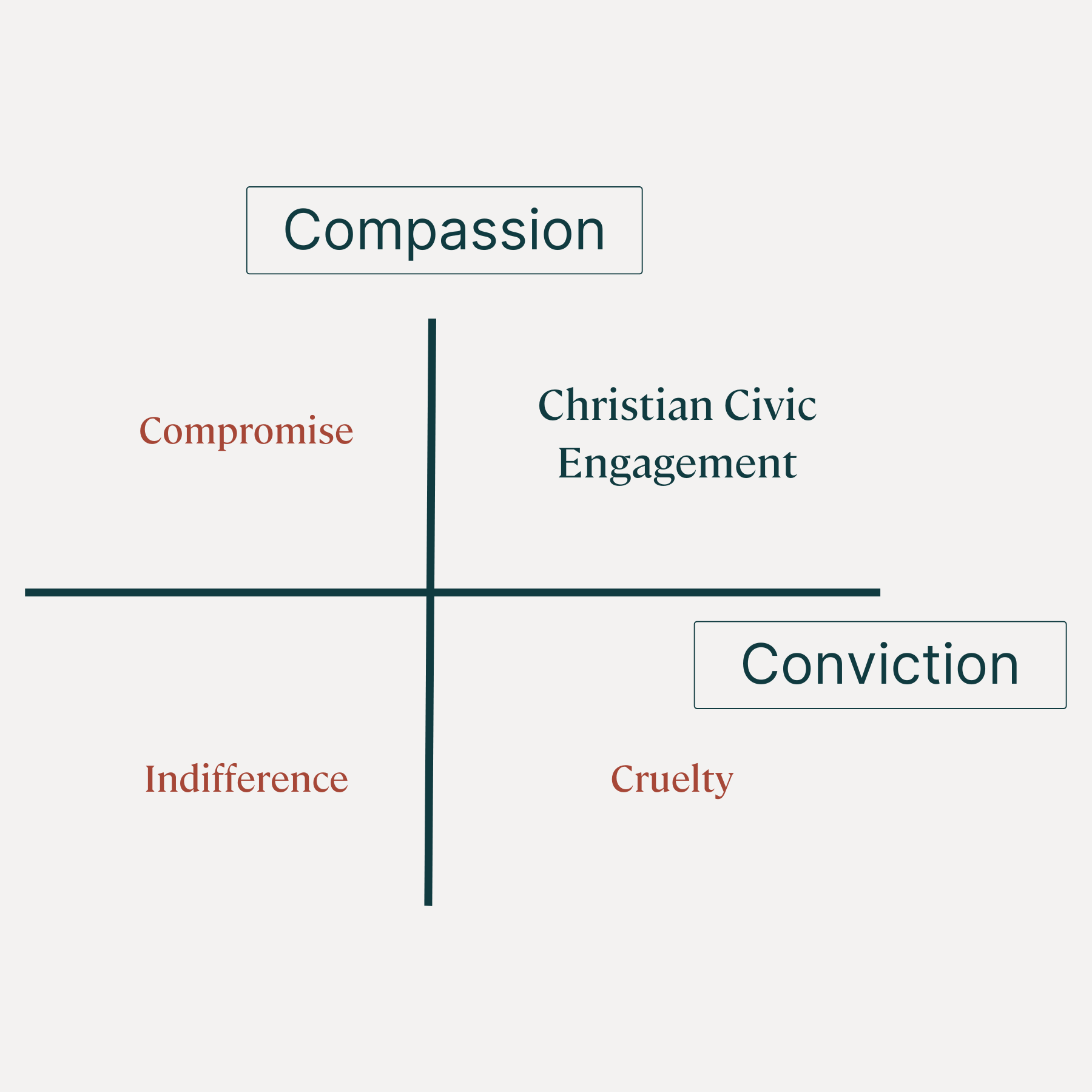

Both compassion and conviction are inadequate on their own. Together, they give us a vision of what God desires. We need them both because:

Conviction without compassion leads to cruelty.

Compassion without conviction leads to compromise.

Without either, we drift toward indifference. Which may feel safer, but is neither loving nor faithful.

When compassion and conviction are held together, they form a Biblical vision for civic engagement that seeks the good of our neighbors without surrendering truth. Jesus is full of grace and truth (John 1:14). He is not half of each, but fully both. We are therefore called to speak the truth in love (Eph 4:15).

Jesus is God’s ultimate conviction. He names sin honestly. He confronts hypocrisy. He exposes false power. He refuses to lie.

Jesus is also God’s ultimate compassion. He moves toward sinners. He touches the unclean. He bears our suffering. And he gives himself for his enemies.

At the cross, conviction and compassion meet. Sin is taken seriously and dealt with completely. People are taken seriously, and our dignity is restored. Justice is upheld, and mercy is poured out.

In our present political environment, the political right is often experienced as cruelty because of its emphasis on conviction without sufficient compassion. The political left is often experienced as compromise (losing its moral coherence) because it emphasizes compassion without sufficient conviction. The gospel offers something neither side can produce on its own, and fulfills what both sides most deeply long for.

The Freedom to Say True Things that Don’t Fit the Age

When compassion and conviction shape us, we gain the freedom to speak true statements that don’t seem to fit neatly into our current political categories. Christians refuse to give in to overly simplistic slogans or explanations that are often meant to attack or discredit rather than build meaningful change.

Because of our commitment to compassion and conviction, we can say…

… the lives of unborn children are worth protecting and mothers and families deserve robust support

… the rule of law matters and restoration should be prioritized over punishment

… true immigration reform maintains a secure border and engages in humane and compassionate pathways toward citizenship

… violent offenders should be removed and immigrants should be honored for their dignity and contribution

… serious fraud in our state should be addressed and dehumanizing enforcement must be rejected

Without a positive vision of civic engagement grounded in compassion and conviction, I have met many Christians who struggle to say both sides of those statements. They have bought into the lie that faithfulness requires “holding the party line” when in reality Christians are not called to hold party lines; they are called to hold parties accountable.

Christians are not called to hold party lines; they are called to hold parties accountable.

Christians should be among the best partners for our civic leaders, working diligently for the common good. And at the same time, we should be among the most confounding, refusing to excuse cruelty or compromise, and consistently calling our leaders back to compassion and conviction.

The ends never justify the means

The gospel teaches us that the ends never justify the means. Immigration enforcement does not justify excessive use of force or inhumane detention. Likewise, the pursuit of justice does not justify violence or hatred.

Miroslav Volf is a Croatian theologian at Yale Divinity School who endured significant injustice in his life and writes in Exclusion and Embrace:

“Forgiveness flounders because I exclude the enemy from the community of humans even as I exclude myself from the community of sinners” [6].

When we strip others of dignity, we quietly give ourselves permission to do them harm. Whether we dehumanize immigrants or government officials, protestors or enforcement agents, we depart from the way of Jesus. The gospel calls us to something better.

Christian civic engagement is not about disengagement, nor about domination. It is about loving our neighbors with compassion informed by conviction, bearing faithful witness to Jesus in the midst of a broken world.

Conclusion

Faithful Christian civic engagement will rarely feel comfortable or satisfying in the moment. It will often leave us feeling misunderstood. We will appear too compassionate for some, and too convicted for others. But this is precisely the path Jesus calls us to walk.

We engage because we belong to a different kingdom. One that has already broken into this world and will one day fully come. We know that politics will not save us. We also know that disengagement will not protect us. As followers of Jesus, we are free to love our neighbors without fear, to speak truth without cruelty, and to labor for the common good without confusing it with ultimate hope.

In a polarized age that so often demands allegiance to the political powers, may River City Church be formed by the gospel instead. We are called to bear faithful witness to Jesus through lives marked by compassion, conviction, and hope.

Works Cited

[1] Justin Giboney, Compassion (&) Conviction: The AND Campaign’s Guide to Faithful Civic Engagement (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2020).

[2] Timothy Keller, Generous Justice: How God’s Grace Makes Us Just (New York: Dutton, 2010).

[3] Stephen Hawkins, Daniel Yudkin, Miriam Juan-Torres, and Tim Dixon, Hidden Tribes: A Study of America's Polarized Landscape (New York: More in Common, 2018), 109-116.

[4] Joshua Harris, social media post, January 2026.

[5] Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” April 16, 1963, in Why We Can’t Wait (New York: Signet Classics, 2000), 77–100.

[6] Miroslav Volf, Exclusion and Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1996), 9.

.png)